Jayson Lusk, farm economist and head of the Agricultural Economics Department at Purdue University, sees the romantic traditionalism surrounding consumers’ vision of food and fiber production as “it should be.” That romantic ideal of smaller farms with a 1940s vision of a farmer in overalls means very real life tradeoffs of lower productivity at higher costs to consumers and higher food insecurity for the people at the lower end of the economic spectrum who cannot afford it.

Lusk spoke at the Bayer AgVocacy Forum Feb. 25, in Anaheim, California, just prior to the Commodity Classic.

“Let’s imagine we want to consume, for example, the same amount of corn we actually consume in the U.S. this year, but doing it with 1950s technology and yields,” Lusk said. “We would need 228 million more acres of land—three times more cropland than we use today to enjoy the same amount of corn we get.” And that’s just one aspect of the conversation with consumers.

Lusk told attendees that going back to 1900 the United States had 6 to 7 million farms, and today that’s dropped to about 2 million farms and yet the population that’s being fed is still growing.

“USDA tells us 2 million farms, but if you only look at those producing any volume of food, that’s about 7.5 percent of that number,” Lusk explained. “So you have 159,000 farms producing about 80 percent of the value of our total agricultural output.” That means that the chance of one of the 33 million consumers in the United States of knowing one of those 159,000 farm entities well enough to ask them questions is miniscule.

That divide is growing every day. And Lusk brought up an interesting phenomenon he’s seen. A consumer’s attitudes about food and ag production tools can run quite closely with their voting patterns. He gave the example of California. The map of votes in the state regarding the proposed ban on same sex marriage—Proposition 8—and the regulation to require labeling of GMOs followed remarkably similar lines.

“If your county voted to ban same sex marriage, there was a strong chance it also voted against the labeling of GMOs,” Lusk observed. “We have to ask ourselves, is this about something deeper than the urban/rural values? Is the vote on GMO labeling really about the science of GMOs or is about something deeper?” While there is something to party loyalty and tribal loyalty regarding political leanings, Lusk proposed that it’s really a disconnect of the demographics that is in play.

There’s also the other question of income inequality and the access to affordable food. Lusk showed a World Engel Curve that plotted the relative income of consumers and the percentage of that income they spend on food.

“The richer you are, the lower percentage of your income you spend on food,” Lusk said. “We spend less than 10 percent of our income on food in the U.S. We still have poorer countries spending 40, 50, 60 percent of their income on food.” In the U.S. a family that brings in $140,000 a year spends less than 10 percent of that on food and spends it on eating out. A family income of less than $20,000 spends 40 percent of that on food and stays in.

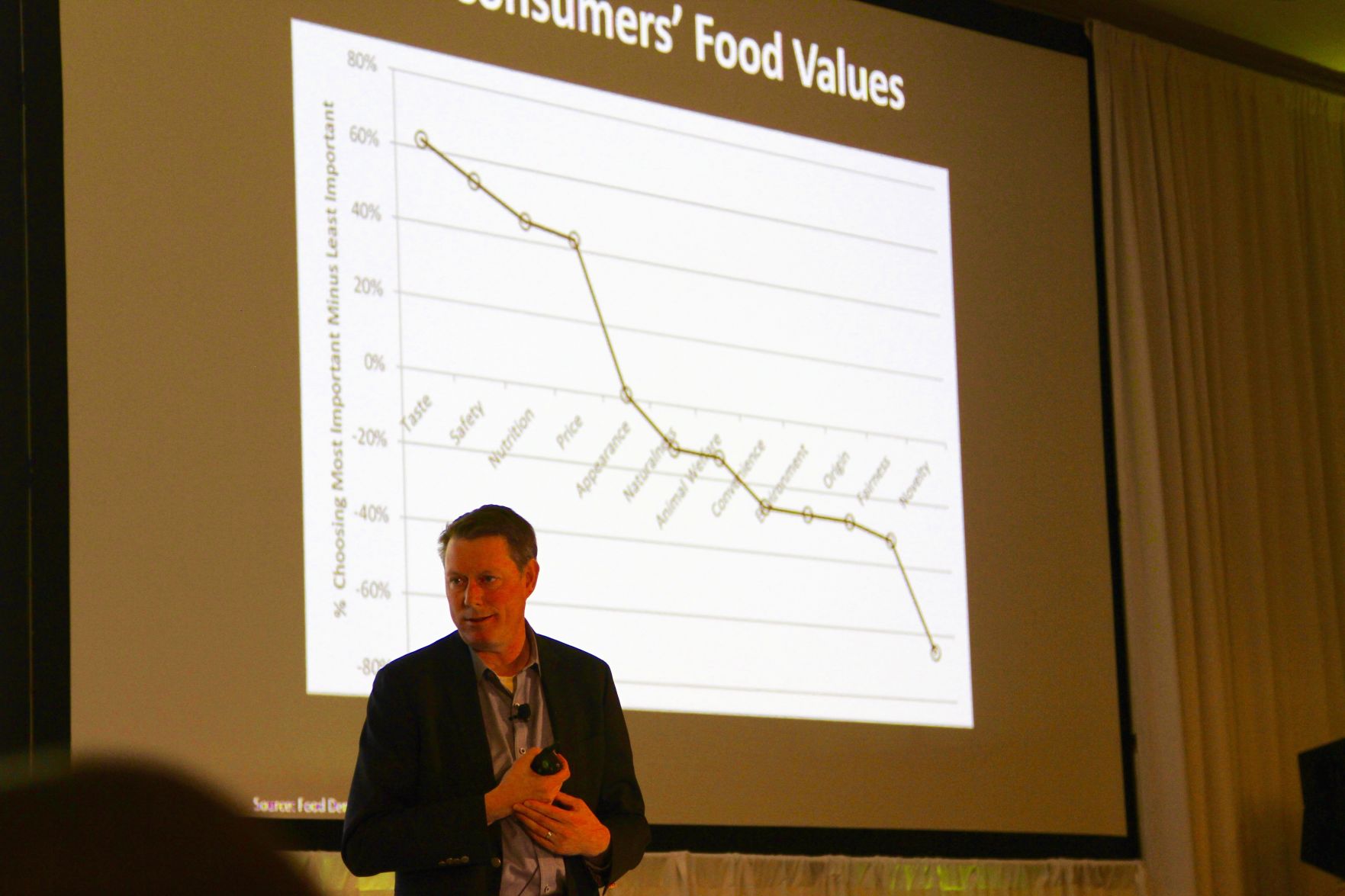

“The food values of the rich in the U.S. put ‘natural,’ ‘nutrition,’ ‘origin,’ or ‘novelty’ first,” Lusk said. “The food values of the poor in the U.S. put ‘price,’ ‘safety,’ and ‘taste’ first.” And yet, the ones influencing the conversation around food production methods are the rich, Lusk observed.

Lusk told attendees that there are big issues emerging that will affect the food conversation of today and the future. Splintering within groups that used to be reliable voices for the industry, like the Grocery Manufacturer’s Association, mean those in D.C. who make the decisions now have to decide whose voice to listen to on topics such as labeling and more. The Heritage Foundation is recently taking on the farm lobby, Lusk said, surprising many since farmers in red states have historically taken conservative stances.

The future of meat demand is also up in the air. Lusk said there’s a strong correlation between political ideology and beef demand, with red states consuming more red meat than blue states. That gap has widened in 5 years.

“Some of these consumption issues are becoming more politicized, and especially if the person is concerned about climate change and animal welfare,” Lusk said. “The U.S. is not likely to see a big increase in meat demand. So if there’s any growth it’ll be internationally. Where we see as incomes grow people tend to add more meat to their diets.” With a lot of venture capital flowing into the plant and cellular-based meat alternatives sector that could potentially affect the traditional arrangements of agriculture, such as corn sales to the cattle-feeding sector.

Technology advancements in traceability and the entry of Amazon into the food market will raise expectations about traceability of food down the road to the farm level, Lusk predicted. With Blockchain and Bitcoin and other technology the information gathered around production of a food or fiber can follow along with it through the rest of the chain to the consumer.

Ultimately, to have effective messaging between farmers and consumers, farmers need to show why they adopted the production technologies they have and help the consumers understand how those benefit everyone.

“They can get on board with sustainability,” Lusk said. “But we need to help them understand the link between technology and the ability to preserve land, preserve water, emit fewer greenhouse gasses.” That just might be a more compelling message, and reach them at the individual level, than just the ability to feed more people on a global scale.

Jennifer M. Latzke can be reached at 620-227-1807 or [email protected].