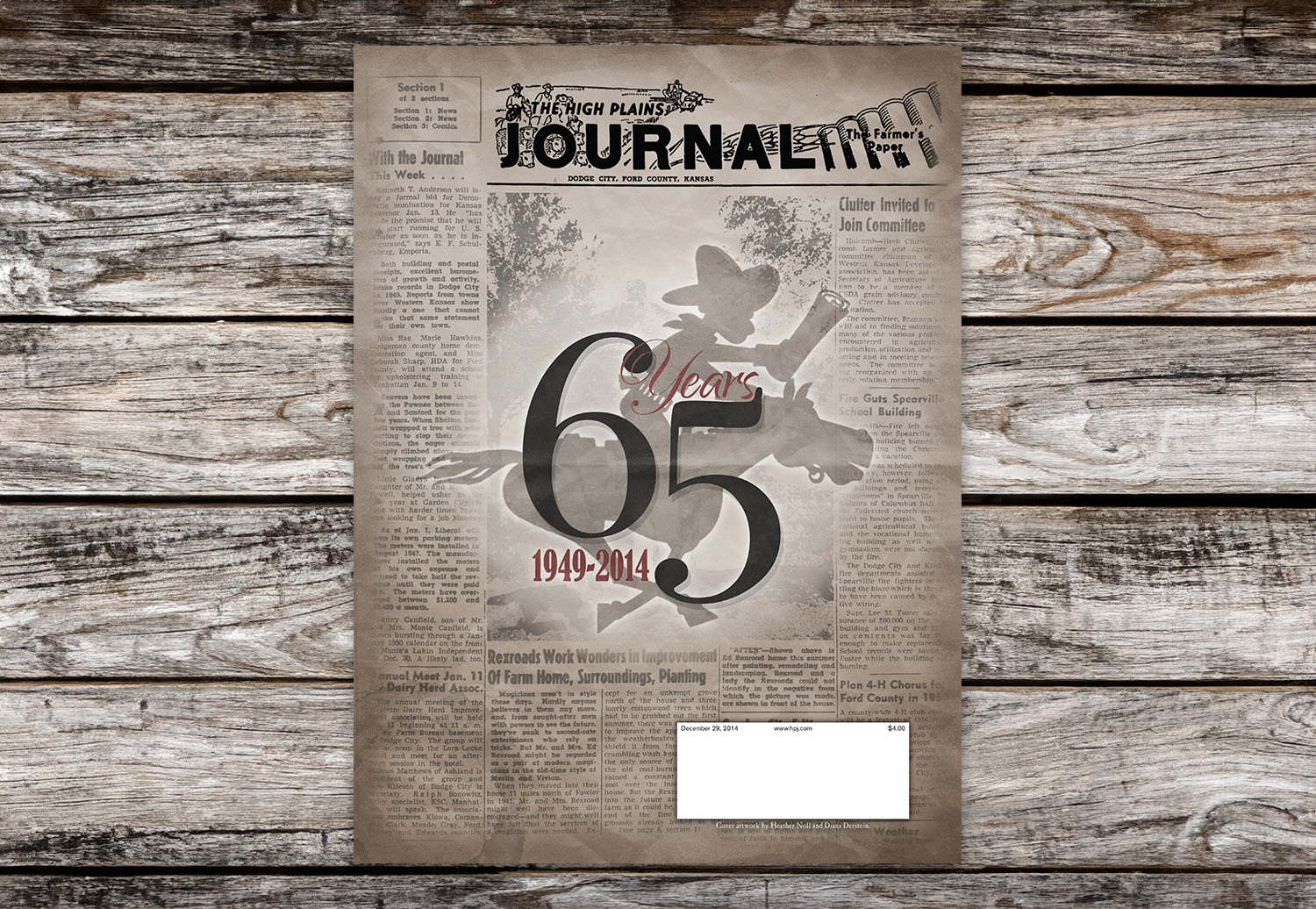

High Plains Journal has been agriculture’s voice for 65 years

In the 65 years of publication under the banner of High Plains Journal, agriculture has undergone rapid change. In times of plenty and success, to times of drought and disaster, the staff of High Plains Journal has been there, right alongside you, telling your stories and educating you about the advancements of the day.

And although trends in agriculture come and go, one thing remains the same—the need for news to help you be profitable and successful in your agribusiness.

1940s

In 1940, farmers numbered 30.8 million, or 18 percent of the U.S. labor force, and there were 6.1 million farms. One farmer fed 19 people, and just 58 percent of the farms had cars. One-quarter of farms had a telephone, and one-third had electricity. When World War II began, rural areas started to see its labor force migrating to war-related jobs in the cities or serving in the military. In 1944, the National FFA (then called Future Farmers of America) reported 138,548 of its young members were serving in the Armed Services. Also, women were working outside of the farm, which led to innovations like frozen food and time-saving home appliances.

The concept of saving time also came to the farm, with advancements in equipment and machinery. In 1942, the International Harvester Corporation introduced its production-ready model of a mechanical cotton picker. In 1947, Frank Zybach developed his prototype center pivot irrigation machine, tapping into the vast Ogallala Aquifer’s water resources and forever changing how farmers were able to produce on the High Plains.

By the time 1949 rolled around, the switch from horse power to mechanization was well underway. Using a tractor, 3-bottom plow, 10-foot tandem disk, 4-secton harrow, 4-row planters and cultivators and a 2-row picker, a farmer only needed to spend 10 to 14 labor hours to produce 100 bushels of corn on 2 acres.

High Plains Journal didn’t officially come into being until Jan. 6, 1949. On that date the very first edition of High Plains Journal was published, with a new format as a farm journal. The newspaper had been in publication since 1883 in some fashion or another, under different names, such as The Dodge City Democrat; the Journal-Democrat; and the Dodge City Kansas Journal.

In 1945, Joe Berkely had come home from his service in World War II and saw a need for a farm journal covering the High Plains region. After working on the staff of the Dodge City Kansas Journal, Berkely, along with Nis C. Petersen, Herbert Etrick, Ross Hogue and Jim Williams bought the paper and changed the name to High Plains Journal in 1949 and created a new banner that depicted the new farm focus of the paper—containing a cowboy, cattle, a wheat harvester and an elevator. Berkely explained the design of the new masthead in his “Editorial Comment”:

“The artist originally had the cowboy to the left tricked out in chamber of commerce, dude ranch, non-working movie clothes and waving his hat in the air, scaring the bejabbers out of the cattle. With a few swift strokes of the pen the cowpoke’s hat was put on his head, he was dressed in the kind of clothes such workmen wear, he was straightened up in the saddle and put to work. The model for this figure was Slim Whaley, calf-roping champion.

The only correction we had to make on the cattle was to turn their horns down. The Eastern artist had created an amazing combination of some dairy herd and the old Texas longhorn.

In the center of the masthead is a self-propelled combine and truck, harvesting wheat. The combine doesn’t look quite like any on the market because the High Plains Journal didn’t want to advertise any particular make. Some details were taken from a picture of a Case, however, furnished by Muncy and Sons.

A stylized wheat head leads the reader across to the storage bins at the right, where the High Plains Journal is proclaimed to be the ‘Farmer’s Paper.’”—Jan. 6, 1949.

In the beginning years of High Plains Journal, there was still a lot of local general news coverage of the community. That very first issue’s cover photo was of Donna Elaine Oden, the “New Year’s Baby” of 1949, along with her mother, Mrs. John A. Oden (formerly Helen Frances Lenz of Dodge City) at the Murray Memorial hospital.

Yet, there were the beginnings of the hallmarks of the Journal’s offerings: Helen Pierce’s “The Kitchen Carousel” column, advertisement for McKinley-Winter Sale Barn and the ever-popular Classified Ads section. Well, perhaps “section” is stretching it—those first classifieds were only a page long. (share an ad here)

That first year, the Journal had five full-time employees and 132 subscribers.

1950s

The 1950s were filled with modern advancements in agriculture and in rural communities. It was the heyday of agricultural and home economic experiments as well as education through the Cooperative Extension Service. Rural electrical and telephone cooperatives were coming online. Equipment engineering was making advancements by leaps and bounds. Farmers were starting to organize to promote their commodity interests both in politics and through marketing, education, research and promotional outreach.

In 1950, there are 25 million farmers, on 5.3 million farms in the United States. One farmer fed 27 people. The push for production was easing up from World War II, but with the Korean War starting to ramp up, the need to produce food, fiber and fuel was on rural America once again.

In 1950, High Plains Journal Editor Ray Pierce, along with Publisher Joe Berkely, worked with wheat farmers to form The National Association of Wheat Growers, even hosting its offices for a time. That same year representatives from 10 states would meet in Denver to organize NAWG, with southwest Kansas wheat farmer Herb Clutter, Holcomb, serving as its first president.

The Journal also served as an incubator for the Kansas Association of Wheat Growers, which in 1951 was known as “The County Wheat committees of the Farm and Ranch Division of the Western Kansas Development Association.”

Sign up for HPJ Insights

Our weekly newsletter delivers the latest news straight to your inbox including breaking news, our exclusive columns and much more.

“County wheat committees of the Farm and Wheat Division, which soon will become the Kansas Association of Wheat Growers, if action of groups who already have held meetings is any indication, are meeting in wheat growing counties to take action headed toward a state meeting Jan. 12.

The committeemen will hold their annual state meeting at Dighton Jan. 12 at 10 a.m. in the courtroom. At this meeting the county representatives will take up ratification of the new name and discuss and vote on an enabling act which has been drawn up by the association’s legislative committee.”—Jan. 4, 1951.

Later that year, KAWG would attempt to pass the Kansas Wheat Bill, which would create a commission of seven members as well as a state levy for wheat of $1 per 1,000 bushels of wheat sold through commercial channels, something that was cutting edge at the time. The concept of producers investing in the future of their commodities was just starting to take flight. While the Kansas Wheat Act was killed that year in the Kansas Senate, KAWG continued to work towards funding research into wheat through its membership dollars. Eventually, the Kansas Wheat Commission would be established in 1957 when the Kansas Legislature finally approved the Kansas Wheat Act.

In his Editorial Comment column, Berkely remarked NAWG was unique in that its membership was limited to those who produce wheat, rather than including non-farm interests.

“This is an era when labor unions are operating at full strength, and in which the atomic processes are beginning to show both forces for good and forces for evil. It is an era when international cooperation may be cemented or may fall with a terrible crash.

In such a period of instability, the fact that wheat farmers find themselves disposed to help themselves, direct themselves, according to the fine program of the national and state wheat groups, to build and maintain stability in agriculture, is an encouraging note.”—Feb. 5, 1951.

The 1950s were a decade for learning, for making the switch from the “art” of farming to the “science” of farming. Extension agents offered help educating farmers on mechanization, farm power and rural electrification, and conducted experiments on new crop varieties and livestock feeding techniques. Extension also helped form and expand 4-H clubs to teach rural families how to farm more efficiently and to improve family life in the home. The pages of the Journal kept focusing on the themes of God, country, family and the farm—much as it still does today.

In 1951, Earl Brookover, Garden City, Kansas, would develop the first commercial feedlot in the High Plains, and together with other cattle feeders kick off the beef feeding industry for decades to come.

In 1954, the number of tractors on farms exceeds the number of horses and mules for the first time, and 70 percent of all farms have cars, half have telephones and nearly all have electricity. By 1959, the efficiencies on the farm would lead to a 30 percent decline in the farm work force, which dips below 900,000 workers for the first time since 1925.

Near the end of the decade, Pete Armstrong from Wichita, Kansas, purchased a controlling interest in High Plains Journal, in 1959.

1960s

The 1960s saw the rise of the Space Race and The Cold War, and with it came more modern technology to the farm and more efforts to expand American farm interests abroad. It was a decade of new efficiencies in labor and the use of crop inputs.

In 1960, there are 15.6 million farmers on 3.7 million farms, down 25 percent from the year before. One farmer now feeds 61 people, up from the nine he fed in 1930. By 1965 it will take just five labor hours to produce 100 bushels of wheat on 3 acres. The decade gives us the rise of hybrid seeds, new farm chemicals to control weeds and pests, and a changing world outside of the farm.

We saw the rise of Norman Borlaug’s pioneering innovations in plant breeding in Mexico. In April 1960, the nation’s wheat growers were on target to raise 977 million bushels, the second largest crop on record back then. Colorado’s crop was expected to yield 51.6 million bushels.

Wheat growers were looking for export opportunities, through grower-controlled market development organizations such as the Great Plains Wheat Market Development Association and the Western Wheat Associates (which would join together as today’s U.S. Wheat Associates.) The Dec. 27, 1960, cover of the Journal showed a delegation of Japanese wheat importers visiting Colorado, hosted by the Great Plains Wheat, Inc., and the Colorado Wheat Administrative Committee.

In the April 19, 1960, Journal, the front cover ran speech by young FFA member Richard Spillman—“Pelleted Feeds Among Great Recent Development in Livestock Feeding.” In the Feb. 23, 1960, issue, the convention of the Colorado Cattle Feeders Association reported members were seeing sizable increases in feed efficiency in fattening steers , but that, “mechanical handling of feedstuffs will be more important in the future. Complete pelleted rations look promising in this area. Results with pelleted high roughage rations show a marked improvement in gain and feed efficiency over loose rations. With high concentrate rations, results have not been as favorable.”

In 1960, 385,000 head of cattle and calves were being fattened in Colorado feedlots, a 14 percent increase from 1959. By the end of the decade, 1968, cattle feeding pioneer Warren H. Monfort’s feedlot would become the world’s first 100,000-head feedlot.

Also in 1968 Roger Tomlinson coins the phrase “Geographic Information Systems,” the precursor of today’s Global Positioning System.

Change was starting to come to the family and community too. In 1969, FFA opened its membership to girls, allowing them to hold office and compete at the regional and national levels.

In the Jan. 5, 1960, Editorial Comment from Ray Pierce, he shared this “New Picture of Rural America”:

“One note of the under-secretary (of agriculture True D. Morse) is right along this line: Farming alone cannot produce adequate incomes and levels of living for families in areas of small farms especially where soils are poor. Recommendations are for encouraging off-farm employment, new industries, assisting farm families willing to migrate, training for non-farm occupations.

…Rural areas, says Morse, are being tied in more closely with urban areas, city people are moving out into suburban communities, power, transportation and communications now serve practically every community and area.

…”Areas will grow, stand still or continue to decline depending upon area leadership. And, the new rural America will be a great stabilizing force. It will continue to give our nation the character in people, the sound judgments and the high degree of good common sense, which has characterized folks who live in the country.”

In other words, changes are coming. We must work together in rural areas to meet these changes and take advantage of the beneficial aspects of them. And we have to continue to supply the nation with the kind of young folks we raise in the rural areas, to supply industry, business, research and executive positions with suitable recruits.”

The Journal also changes in this decade. A 1964 ad rate card shows the publication has branched out into four editions covering Kansas and Colorado: Northeast Colorado, Southeast Colorado, Central Kansas and Western Kansas. Then, in 1965, after the Arkansas River floods the Journal’s offices in downtown Dodge City, the company moves to a new location on the east side of town. A new plant is built and the permanent home of High Plains Journal is set at 1500 E. Wyatt Earp Blvd.

1970s

During the mid 1970s, there were reports of record farm export values and prices. Meat production was at a record high. Articles touted food production was likely to increase. Wheat stocks were up, yet producers were looking for better markets. Cattlemen were facing new challenges in Washington, according to the American National Cattlemen’s Association. “It seems pretty obvious the beef cattle industry is headed for nightmares on Capital Hill,” Wray Finney, first vice president of ANCA said in a February 1975 High Plains Journal. Cattlemen must choose to sell now or wait in hopes of higher prices.

Other articles advised farmers that proper management and efficient operation of their farms will help curb inflation. Farm debt and land capacity was analyzed in other issues. Other energy sources were discussed. Despite these issues, one farmer still fed 72 people.

Wheat farmers were unhappy with prices. Some organized “plow down” or destroying wheat acres to encourage prices to rise. Producers wanted to work up 10 percent of their crops. One ad stated, “It’s time to fight for better wheat prices.” Another story in an early February 1975 issue was headlined, “Orderly marketing of wheat will help stabilize and should improve prices.” President of the Colorado Wheat Administrative Committee Don Wisdom said, “If farmers will continue to supply a constant flow of wheat, without flooding the market place, the price situation will stabilize and should improve.” Many struggled with hunger in other parts of the world and how farmers can help feed the rest of the world.

Other topics found in Journal pages: New corn hybrids. Fertilizer supplies. Energy needs. Record farm export value. Soviet grain consumption. Record farm prices. School lunch rules. Ag research. Farm debt load capacity. Oversupply of cattle/high feed grain costs. Seed shortage. Consumer demand.

1980s

A dark time started for farmers and ranchers in the 1980s. Those farmers with a heavy debt load were often times found without a field or a tractor to plow. Droughts in some parts of the country hindered crop production progress. By 1987 farmland values bottomed out. Farm Aid concerts to benefit the American farmer were started in 1986 through 1988. One headline, “Urbanites don’t understand farm crisis,” explained what the regular world was thinking. Another, “Putting American ag back to work is central issue,” provided hope.

The Journal changed editors in 1983. Longtime Editor Ray Pierce retired and Galen Hubbs moved to the desk.

By 1985 reports in the Journal said it was a time to get into farming with less capital. “It isn’t a bad time to start farming,” a story in the April 29, 1985, issue said. “Young farmers won’t need much capital to start.”

In the proposed 1985 farm bill, farmers would need to slowly adapt their operations to fit the market. One story with a High Plains congressmen said, “We firmly believe it’s going to take bipartisan action to resolve the farm problems.”

Scientists warned of global warming. One of the worst droughts hit the Midwest in 1988. More farmers began using no-till or low-till production practices. Biotech became more viable for crop production and livestock producers. During this time period, one farmer fed 112 people.

There were declines of rural population noted in the 1980s, even though the previous decade saw increases. Families were starting to see the effects of “selling the farm.” One Journal article reported stress was taking a toll on farm kids. “Long accustomed to sharing the responsibilities and joys of farm life, farm children have begun to share in the stress that is wracking many family farms, bringing with it foreclosures and the loss of their family’s way of life.”

Other issues of note in Journal articles: Products to improve yields. Large cotton supply. Subtheraputic antibiotic use in cattle. Export enhancements. Computer systems to improve efficiency. Farm auctions down. Crop insurance premiums. Wheat exports. Female farm operators. Income protection.

In the Jan. 3, 1983, issue of the Journal, Editor Ray Pierce talked about the 100th anniversary of the publication that would become the High Plains Journal. In 1883 the Dodge City Journal was established, and over the years went through many incarnations, until 1949 when the name officially changed to High Plains Journal and it began reporting ag news along with local features. The local flair was eventually phased out completely.

Pierce wrote,

“On this 100th year of our birth, we expect a very interesting future for agriculture. Leading all other issues, we expect that emphasis will be put on ensuring an adequate income for our farmers and ranchers. Looking into that tricky crystal ball for revelations about this issue, we see more unity among people in agriculture on prime issues of this kind. We expect to see developing a program of public relations like those that have delivered so many benefits to labor and industry. The community of small towns and rural agriculturists and families certainly have a story to tell and a product to deliver that is important to the nation’s defense, wellbeing and prosperity.”

1990s

The U.S. Department of Agriculture saw a reorganization in the early part of the decade and finished it out with release of organic standards.

In the beef industry, a concentration of packers was beginning to worry livestock producers. One article in the Jan. 8, 1990, issue stated, “Today ConAgra, IBP, Excel and National Farms control 80 percent of slaughter beef market, and ConAgra, IBP and Excel control 85 percent of the boxed beef sales.”

Cattle movement was good in the early part of 1990. In the Jan. 15 issue, Larry Dreiling photographed the pens at Winter Livestock, Inc., in Dodge City, Kansas, during their record setting Jan. 10, 1990, sale. The barn set a new one day sales record at the nation’s largest independent cattle auction. Ray Winter, auction manager, said 15,091 cattle were sold.

In 1998 and 1999, there was a price slump because of crop surpluses, when in years previous, farm incomes set records—1996 it was a record $54.9 billion.

Rural counties gained population in some areas of the nation.

Farmers began using more information technology and precision technology when making farming choices and then with production practices. One farmer fed 129 people.

Other topics appearing in the Journal: Wheat market values. Test tube-type calf born. Environmental issues. Consumers make changes/food purchases. Budget cuts. CRP acreages. Beef checkoff benefitting cattlemen. Trade barriers. Ag outlook.

On Jan. 1, 1994, Joe Berkely retired and Duane Ross takes over the role of publisher.

2000s

The new Millennium brought rapid change in the technology of agriculture, and with those technological advancements came rising consumer interest in how and where their food is produced.

At the beginning of the decade, equipment manufacturers were just starting to roll out precision agriculture equipment. By the end of the decade, farmers hardly knew how they’d farmed for so long without GPS systems, AutoSteer and yield monitors. One farmer fed 139 people.

In 2003, Mark Zuckerberg creates Facebook in his Harvard dorm room. In 2006, Twitter comes online. “Social media” begins to dominate conversations and will forever change how consumers and agricultural producers relate. The 2000s give rise to the “food blogger” and a host of other niche blogs. Anyone with an Internet connection and a dream could become an “expert” overnight. This in turn leads to conflict in the food production industry. Consumers, concerned about crop chemicals, livestock antibiotic usage and other issues, begin to shape how farmers and ranchers produce crops and livestock.

Journal editorial staff start Tweeting and posting Facebook updates at conventions and other events throughout the decade.

During the latter part of 2003, there were concerns about bovine spongiform encepathalopathy and whether or not there was beef infected with BSE that had made it into the U.S. food supply. On Dec. 23, 2003, the “cow that stole Christmas” was the first one in the United States found with the disease. Beef markets and cattle producers suffered following the discovery and testing of further cows suspected to have BSE.

In early 2004, livestock producers were gathering information about the U.S. Animal Identification program, and consequently the program was released at nearly the same time as the discovery of the first U.S. BSE case.

“I reassure you today, that there is a justified need for an ID system. It could provide a fast tool for rapid containment of an emerging or intentionally placed disease,” Dale Blasi, Kansas State University professor and beef specialist said in a February 2004 Journal. “It’s about health detection—not about trade.” The two issues are separate, he said.

The decade also saw changes at the Journal. Editor Galen Hubbs retired in 2003, and Holly Martin moved into the desk—the third editor in the history of the Journal and the first woman to hold the post. Then, in 2007, Publisher Duane Ross retired and is succeeded by Tom Taylor.

2010s

Drought, flooding (in some areas) and wildfires prevailed 2011 to 2013. Heat and no rain dominated the pages of the Journal. Farmers and ranchers learned new ways to stretch what water they had or how to keep ahold of their cowherds. One farmer fed 155 people.

Journal Editor Holly Martin wrote in her July 2011 column,

“You know when ‘experienced’ farmers are saying things like, ‘This is as bad as I can remember,’ the drought in my part of the world is bad. One thing is for sure: I’ve never seen anything like it.

The grass is brown. And when I say brown, I mean it looks like the dead of winter. The weeds aren’t even growing. The ponds dried up months ago. People are selling their cows. The flies aren’t even that bad—except in the places where they can find a little water. I have not had one mosquito bite all summer long.

When one of my farmer friends was asked about his irrigated corn crop, he said, ‘It’s tough.’ That might be the understatement of the year. While irrigation is keeping the crops from looking like the dormant pastures, they still need the help from Mother Nature occasionally.”

In 2012, the Journal enters a new era in publishing and rolls out its digital edition for tablets, computers and mobile devices. And, in 2013, the printed Journal undergoes a redesign that includes more use of color and other advancements.

Kylene Scott can be reached by phone at 620-227-1804 or [email protected], and Jennifer M. Latzke can be reached at 620-227-1807 or [email protected].