Agriculture’s balance sheet in 2025

(Photo by Tom Fisk via Pexels.)

You can see it on the faces of many farmers in America right now: stress; fear of the future; responsibility for multi-generational operations; and a demand to pinch pennies in 2025. Analyzing the net farm incomes of the last three years paints a bleak picture.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s December 2024 farm income forecast, net farm income is projected at $140.7 billion for 2024, down 4.1% from 2023 and decreased 22.6% from 2022—when it hit its peak at $181.9 billion. After accounting for inflation, 2024 net farm income fell 6.3% compared to 2023.

American Farm Bureau Federation economist Bernt Nelson said 2024 was a challenging year for farmers, and 2025 is full of unknowns that could affect farm revenue in multiple ways. Nelson said grain producers in the Midwest have faced the most difficulty due to low commodity prices in conjunction with higher input costs.

“We saw a little bit better profitability this year than in 2023, but the losses in 2023 were so substantial that it will take years to make up for this,” Nelson said. “These lower prices have continued, but now there’s a little bit of a carry in the markets for our corn and soybeans. When we see 450 to 460 for our futures prices in corn, this will help our farmers a little bit, but it’s still very difficult to be profitable at these levels.”

Nelson said the minor improvements that have figured into net farm income forecasts are the result of high cattle and poultry prices.

“We’re looking at a cattle inventory that’s at the lowest it’s been in 73 years,” Nelson said. “These prices have come up, and consumer demand has remained strong. U.S. consumers are still eating a lot of beef, and that’s helped keep some of these net farm income numbers elevated a little bit.”

However, Nelson said livestock diseases—such as New World screw worm and highly pathogenic avian influenza—could make cattle and poultry prices vulnerable in 2025. They are just more unknowns to add to the list that could affect farm income this year.

A repeat of the 1980s Farm Crisis?

Nelson said the position the farm economy is in right now bears similarities to the 1980s Farm Crisis—which is known as the worst farm crisis since the Great Depression.

“In the ‘80s, we had inflation that ran wild,” Nelson said. “We were planting fence row to fence row, and we produced a lot of grain. There were some years when farmers reaped the benefits of very, very high prices, but that inflation caught up with them.”

Comparing the ‘80s to present day, Nelson said inflation has been a significant factor in the current financial situation, particularly when it comes to input costs. Although it has subsided since it reached 9.1% in 2022, Nelson said it is still affecting farm profitably.

“We have to remember that inflation is a rate of growth,” he said. “We’re still feeling some exhaustion from inflation on our input costs, but the No. 1 thing that we’re looking at here this year is lower grains prices with these elevated input costs.”

Looking back to the ‘80s, Nelson said the biggest difference between now and then is land values.

“When we produced that much grain, and prices crashed, we were left with these extremely high interest rates and a very low-value crop,” he said. “Because of those high interest rates, land values dropped. That left people without the ability to use credit. When you don’t have land to borrow against, that limits what you can use as collateral, so your loan values go down, and that left a lot of guys in the bankruptcy situation.”

In 2025, land values have not dropped off, and farmers are still able to able to use them as collateral. Nelson said this will be helpful going forward when it comes to credit quality. Similar to the difficult financial times of the ‘80s, Nelson said profitability and liquidity are top of the mind for producers and lenders right now.

“We’ve got a lot of parallels right now with the Farm Crisis of the 1980s, but we’ve done some things that show that we’ve learned some lessons from the past,” he said.

The American Relief Act and a farm bill

In December 2024, Congress passed the American Relief Act of 2025, which provides farm relief payments and financial support for those affected by the challenging farm economy. The U.S. Department of Agriculture is required to distribute the funds within 90 days of the bill becoming law.

More than $9.8 billion in payments per acre will be provided for 20 crops, including corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, rice, grain sorghum, barley, oats, peanuts, sunflower seed, canola, lentils, dry peas, flaxseed, large and small chickpeas, mustard seed, rapeseed, crambe, safflower and sesame seed.

“The economic aid package will go a long way in keeping us from going down that same rabbit hole of the Farm Crisis of the 1980s,” Nelson said.

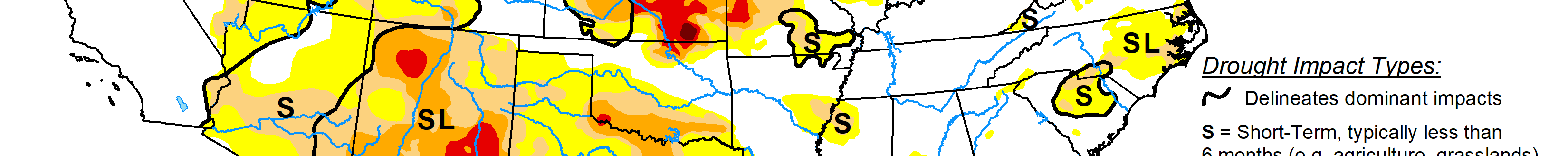

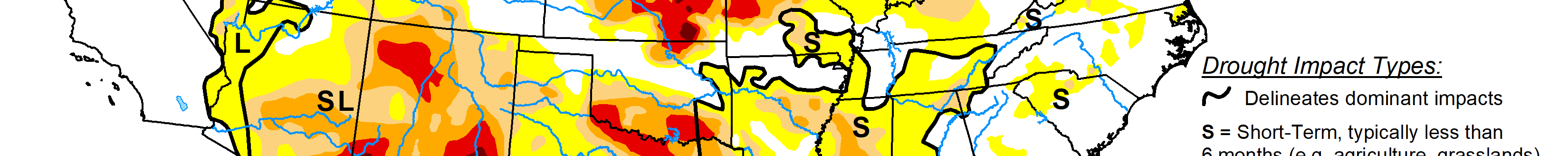

The act also includes $21 billion for natural disaster recovery, including losses from droughts, wildfires, hurricanes and floods in 2023 and 2024. An additional $2 billion is set aside for livestock producers affected by drought and other severe weather conditions.

Congress also passed legislation to extend the current farm bill—that was signed into law in 2018—through Sept. 30, 2025. This also prevented a costly government shutdown that would have been imminent. Nelson said a new farm bill in 2024 would have been much more beneficial to agriculture and the current financial situation agriculture is in.

“The reference prices relative to where crops are now are outdated,” Nelson said. “The safety net just isn’t there. When you have holes in your safety net, farms can fall through. We have programs that are going to be underfunded going into the next year, and that’s going to be a real problem. Without that, we’re going to continue to see a farm bill that’s not as effective as it could be.

“When we look to 2025, a new farm bill is going to be one of the top priorities for the ag economy as a whole. We have to get it updated and across the finish line. There is going to have to be bipartisan cooperation to get this thing done, and we need it now more than ever.”

Trade and tariffs

With the recent inauguration of President Donald J. Trump, changes are imminent for America. Many in agriculture are concerned about decisions surrounding trade and tariffs specifically—which could have ramifications for trade relations, exports and prices.

“I think what we know about the Trump administration is that it’s always full of unknowns,” Nelson said. “We know trade and tariffs in relationship to our trade partners are absolutely on the table.”

Tariffs are a tax tool often used to level the playing field for certain goods, but they can have major consequences to other industries—namely agriculture—once the dominos fall.

“A trade war would add significant financial strain to the already struggling and vulnerable ag economy,” Nelson said. “I don’t think we’re going to be able to get answers there until some of it starts to play out, but ultimately, tariffs are a dangerous thing for agriculture.”

Nelson identified the U.S.’s largest trade partners as China, Mexico and Canada, and implementing tariffs could produce ripple effects within agriculture. For example, Nelson said Mexico is a critical trade partner for the pork industry, and tariffs could upset past export relationships.

“About 40% of our overall pork export market goes straight to Mexico,” he said. “If we implement some tariffs, and we find ourselves with some trade implications from our biggest trade partner in pork, this will be a really big deal for our hog farmers going into 2025, and so these uncertainties are definitely top of the list when we look at what is happening going next year.”

Money management

Nelson said the managerial decisions farmers make in 2025 could be the difference between bankruptcy and holding on until the farm economy improves. Many farmers are renewing their operating notes with the bank right now, and input costs keep going up. Nelson highlighted preserving working capital as the most important strategy to keep farms viable for the next year or two.

“Cash is king, and it’s the most liquid thing that you can have in a situation like this,” Nelson said. “I’m not saying don’t spend any money and go dig holes and bury your cash, but when we evaluate our decision-making going into the next year, we need to be investing in productive assets. This is not the year to try something that’s experimental, like a chemical that promises a 3-bushel-per-acre yield boost without a lot of data behind it or go buy a second payloader, because you think it would speed things up. We need to be critical in our thinking about what we spend money on.”

Nelson said even though interest rates have fallen a bit, they are still in the range of 6.5% to 7% on operating loans. Farming requires a great deal of cash flow to stay in business, but interest almost always contributes to a deeper financial hole.

“If a farm has a $250,000 loss, trying to figure out how they’re going to be able to pay for getting the crop in the ground in the upcoming year and still make those payments is a pretty tall order,” he said.

Nelson said many farmers are looking into refinancing options right now, and many believe credit will start to deteriorate over the next year. He expects to see a great demand for loans due to difficult financial times.

“There’s still enough quality in our credit sector that approval rates should still remain,” Nelson said. “They’re going to see some losses, but they should still remain pretty high over the next year. What this means is this year we’ve still got options. There are refinance options that, while they are costly, may help keep a farm.”

Nelson reminds farmers what refinancing can do to equity in the long run and consequences of short-term fixes.

“When we’re only making interest payments, we’re not paying down any of the capital on our land or other debt, and that means we’re not building equity, we’re actually eating into it,” he said. “This causes problems with working capital and cash flow. Make sure you have a marketing plan and know what your options are if you end up in a pinch and have to decide whether or not to spend some of that capital. Those are the types of decisions that are going to make or break people going into the next few years, and the ones that approach them in that way are the ones who have the ability to be the most optimistic.”

Lacey Vilhauer can be reached at 620-227-1871 or [email protected].